Sound = sonic element

In the complex sonic environments that we inhabit, one is constantly bombarded by an array of sounds. Analysing them as waves and troughs highlights the overlap and seemingly unidentifiable jumble of noise that meets our ears. Recording studios go to great length in isolating sound, designed to minimise reverberation and exclude and separate various sounds. Yet – astonishingly – we can discern varied sounds in a complex sonic environment. We can have in-depth conversations in the most unsuitable of situations. This is due to the brains unique ability for pattern recognition. Sounds are discernable and in this sense have a strong link to those elements that they are associated with - sonic-elements.

Soundsapces situate & orientate

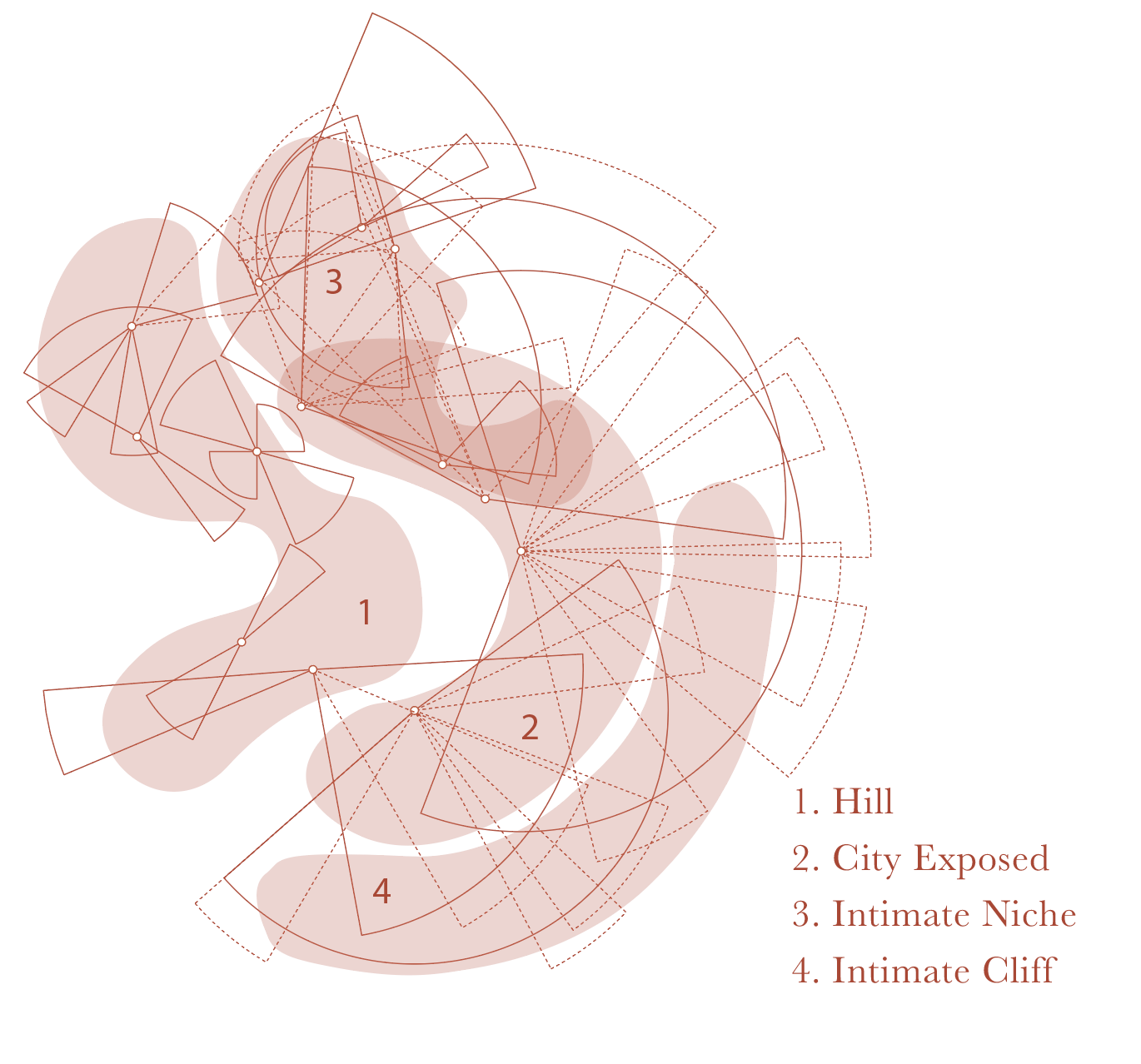

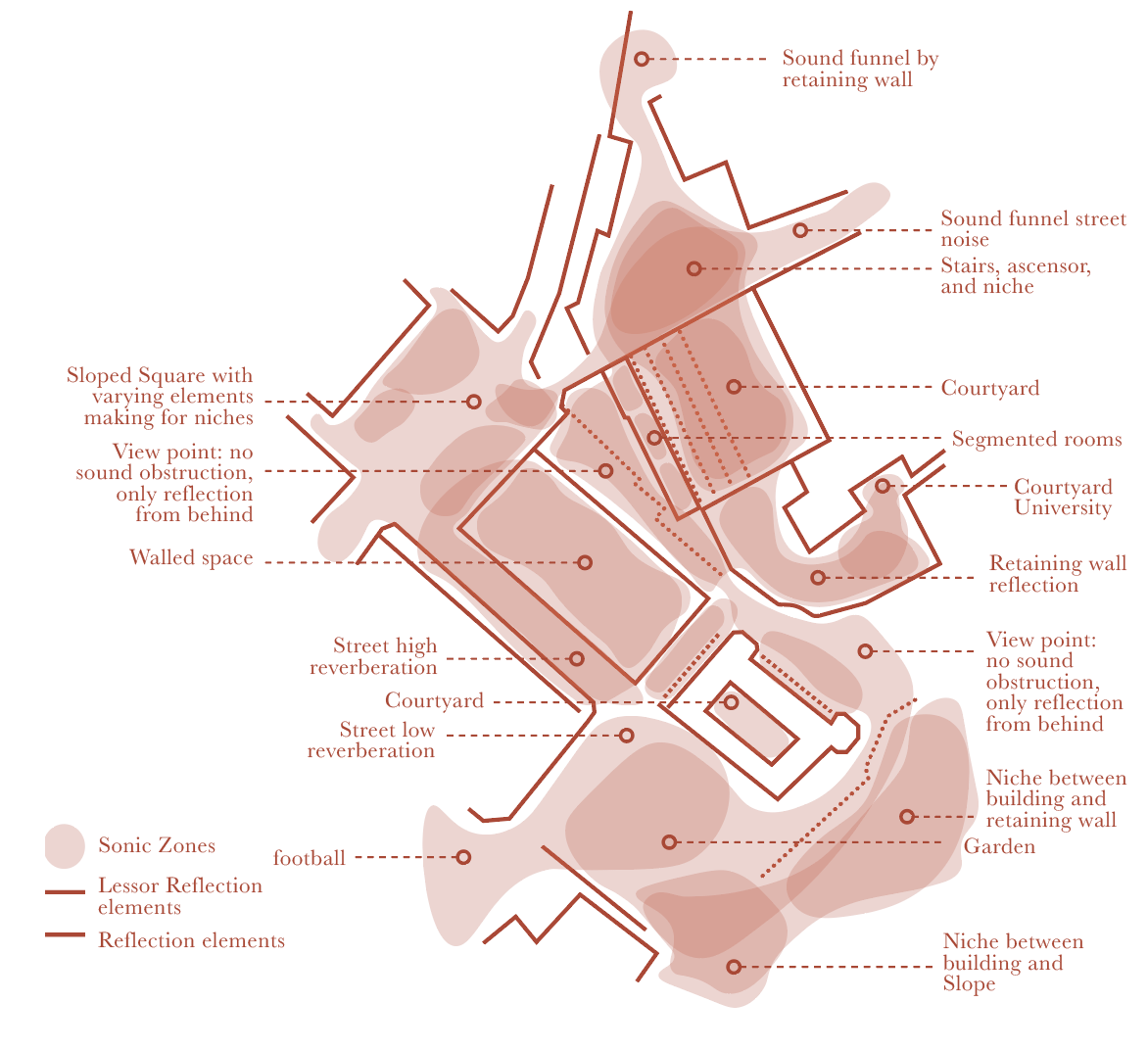

Soundscapes exist beyond the visual realm. They are composed of varied sonic elements that form an environment, a spatial composition. These ensembles are composed of how sounds interact with an environment and intuitively offer an understanding of dimension, materiality and space. As Pallasmaa (2017) describes the ability of sound to orientate and situate, he highlights how in the dark the dripping of water carves out a void in our imagination – Sound gives form. Yet soundscapes also place one in the world – in our socio- cultural landscape. Sound as a composition constructs a sense of place – it not only positions one in space but also gives an understanding of what that space is. It allows one to form a nuanced awareness that is unattainable through sight.

Soundscapes are Affective

Blesser (2009) draws a clear distinction in defining aural landscapes as a phenomenon of experience - that sound is able to be measured and quantified yet it is the intangible ability of sound to AFFECT us which is critical for architecture. It’s affective quality, not only influences how one feels but also how one acts in response. It reverberates through us physically, directly engaging the body and influencing how one physically feels. It also stimulates memory, drawing on past experience as well as engages our sense of being, stimulating emotional and cognitive responses. Collectively these attributes of sound position soundscapes as highly experiential and in turn impactful environments.

Sound as an Act

To listen and to make a sound is both an act. Underappreciated, these acts are fundamental to how we navigate the world and this has been informed from a long lineage of cultural influences. To walk softly in a library, or scream at the top of ones voice in a protest, to change the way one talks in a crowded elevator. These actions seem natural - unconscious – however, it is closely linked to behaviour in social and environmental circumstance. We readily adjust the tone and level of our voice or the manner in which we listen according to the situation. Ganchrow (2017) highlights how we do not simply listen, but actively listen by making gestures and sounds that denote the act. During an a cappella performance in a small space or a church, this is pronounced as one is aware of ones own presence – holding in the sneeze to the end of performance. The extreme situation however is true of the everyday as one navigates ones own interaction with collective sounds and society. The notion of presences is linked to the act as to make a sound is to alter the soundscape and denote ones existence. In this sense sound as an act is closely linked to behaviour and presence.

Soundscapes as spaces of appearance

The space of appearance as the public body, a temporal definition of seeing public space as a verb rather than a noun draws to the fore the interaction of sound in the landscape of the city. Sound as an act, drawing forward the notion of presence highlights how individuals create the public through their interaction with-it. Examples in Valparaiso are; the beginning of the student protest where the hills and city both filled with the sound of clang metal as citizens throughout the city supported the movement; or the end of the America’s cup where horn’s and shouting resonated through the city as a amphitheatre for celebration. Sound expands the public realm into the home as it permeates walls and ones private domain. It is the everyday where sound as an act is seen as a constant mediation of society. In the words of historian Peralto (2009), “Valparaiso is place of harmonic disorder”, where chaos remains in careful balance.

ACT | Sonic Presence

Soundscapes exist beyond the visual realm. They are composed of varied sonic elements that form an environment, a spatial composition. These ensembles are composed of how sounds interact with an environment and intuitively offer an understanding of dimension, materiality and space. As Pallasmaa (2017) describes the ability of sound to orientate and situate, he highlights how in the dark the dripping of water carves out a void in our imagination – Sound gives form. Sound as a composition constructs a sense of place – it not only positions one in space but also gives an understanding of what that space is. Yet soundscapes also places one in the world – in our socio- cultural landscape. It allows one to form a nuanced awareness that is unattainable through sight. Sound is presence, of oneself and of others.

As an act, presence is underpinned by a relationship through which sound is a medium. To listen and to make a sound is a means to engage this medium and draw attention to presence. Presence as an act, is composed of two counter acts. The first is focused on oneself as being (The act of Sonic Intermission) which is opposed the second that is external and orientated to being present in the world (the act of Sonic Intervention).

Sonic Intermission

Pallasmaa (2017) advocates that forming tranquillity is one of the objectives of architecture. The notion positions quietness as being an act that draws attention to being. Expanding on this, Granchow (2017) defines quietness not as the lack of sound but rather the lack of response (Granchow, 2017). The position situates the auditor in a reflexive environment, where presence is orientated on oneself. Importantly, quietness is situated not as a space devoid of sound but rather emphasises the act as simultaneously being separated from the world unable to intervene in it and being witness to it in a state where it does not respond to the auditor.

The act manifests in daily life in numerous ways and is orientated toward the notion of intermission as being an intentional break as moment of respite. Going to the church, sitting and watching over the city or a walk along the promenade and even the bombardment of the electro dance floor when dancing by oneself are all such moments of intermission. Here we position the interaction with sound as being not quiet, in the strict definition of the word, but rather sound which one cannot intervene in and rather only be affected by. The position seems counter intuitive, yet the notion of tranquillities objective which Pallasmaa (2017) positions is to draw emphasise on being and thus it is rather a tranquillity of the mind and self, in a state of meditative reflection.

Sonic Intervention

The act is one of intentionally intervening in the sonic landscape. The definition is broad and encompasses a wide range of interventions, from performance artists, installations, protests and even less noticeable interventions such as altering the ambience of space. Those engaging in the act are positioned as composers due to the notion of sound being part of the space of appearance – the public realm. These acts intend to affect and alter group behaviours. The sonic intervention is thus closely linked to the commons, as it becomes a collective act where by the composer is in constant dialogue with those who are interacting with the sonic alteration. Opposed to the act of intermission, intervention calls for response.

To make a sound is to draw attention to ones presence while to actively listen is to recognise that presence. Sonic intervention is thus a relationship. Sounds ability to exceed the normative notions of the public realm, situates the act as not being defined by public or private boundaries but rather is seen as a common – a space of sonic mediation. Any sonic act, including silence, is in itself an act when seen to be deliberately and part of the collective. This positions the commons as being a navigation of various sonic instances and actors. Appropriation through sound is widely accepted in Valparaiso, as various composers of space exist.